The Rising Costs of Conservation

Wildlife held in the public trust: It’s a cornerstone of the North American Conservation Model. The phrase sounds good, but what does it actually mean in regards to upland birds and upland habitat? Simply put, it means that every wild Sharptail in Montana belongs to the citizens of this country. The Blue Racers of Oklahoma and Texas belong to everyone. We are responsible for the Ruffed Grouse of Maine and the Bobwhite of Louisiana. The public land on which they reside is in our care as well. It is our responsibility and our resource. Regardless of whether or not these birds are in our back yard or on public lands, if they are wild, they are our charge.

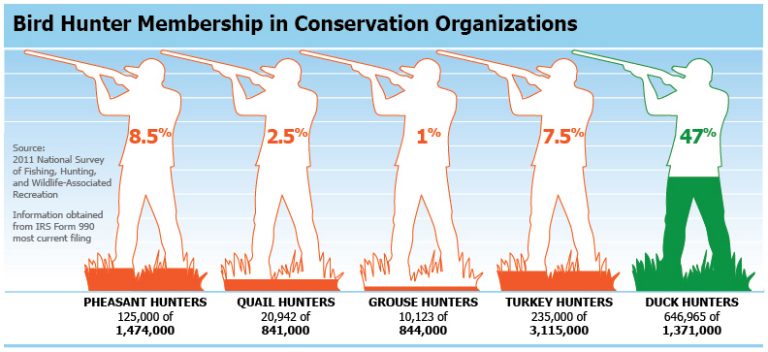

Hunters are an irreplaceable force for conservation. License fees, excise taxes on ammunition and firearms, and donations to hunting conservation organizations account for $1.6 billion in annual funds for wildlife and management of those resources. We are able to wear this contribution as a badge of honor – it’s something we use when talking to non-hunters to demonstrate our responsibility and stewardship of wildlife. The license fees and Pittman-Robertson funds account for over $1 billion being utilized by state wildlife agencies. But annual budgets for National Forest Service , National Parks, BLM and NWR alone exceed $10 billion a year and does not account for individual state budgets. A closer look at the numbers reveals a growing gap between our conservation ethic and our talking points.

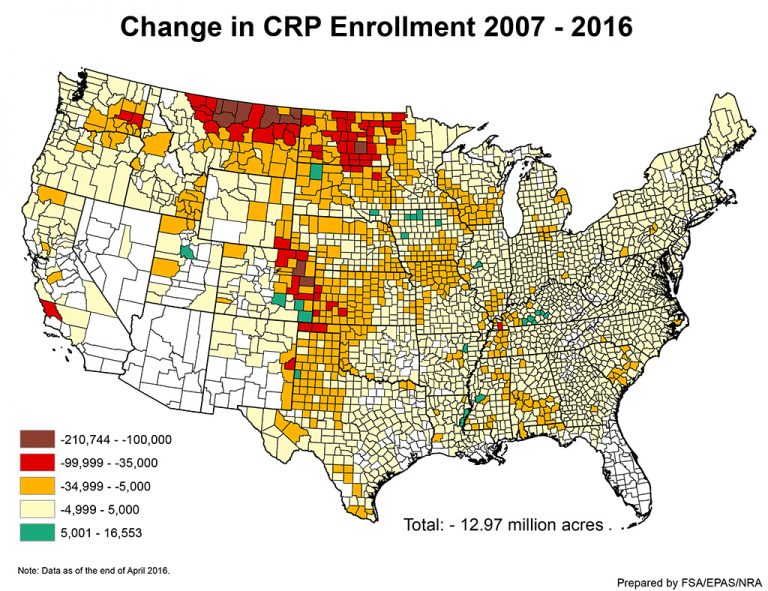

Wildlife is a resource that both costs and generates money. Wildlife as public property is how state and federal agencies view the game they manage. The costs of conserving these resources are increasing. For upland birds, the effects are two-fold because the drivers of much of this cost increase – land and fuel – are the same things removing upland habitat from the landscape. An acre of residential land cost $84 in 1958. Today that same acre of land costs $6200 – 73 times more expensive. Gas, which cost 30¢ per gallon in 1958, has seen prices well north of $3 in recent years. An item that cost just $1 in 1958 costs $8.09 today.

It takes a lot of people-power to implement effective changes to habitat and manage wildlife resources. The average annual wage in 1958 was $3,674 compared to $44,880 now. To somehow believe that nature is wild, free or should be free is to be stuck in a centuries-old mentality where human activities were part of a self-sustaining ecosystem, not shaping it. Maintaining a resource is always less expensive than having to rebuild it. Unfortunately for upland habitat, rebuilding is the space we find ourselves in, where much has been destroyed, taken away. Decades have passed, and just now we’re awaking to the impacts on the broader ecosystem.

Hunters are faced with this reality: slight gains recruiting new hunters will not increase license sales and equipment sales to the point where conservation can be wholly funded by the sportsman, and it never has been. The reason we shoulder a disproportionate percentage of the cost of wildlife is because we’re passionate about it, knowledgable and care enough to pay more. Working against hunter funding are the skyrocketing costs of conservation. Land prices driven upward by commodities and development, the cost of fuel, equipment and labor for habitat improvement, the ongoing costs to monitor and manage are all increasing with fewer hunters to foot the bill.

According to over 50 years of license sales data available from the US Fish and Wildlife Service, in 1958 hunters comprised 8.08% of the US population. The highest number of individual license holders occurred in 1982, when there were 16,748,541 licenses sold, making up just 7.23% of the 231 million populace. Since 1982, license holders have decreased in number as well as a percentage of the total population. In 2013, there were 14,631,127 license holders representing 4.63% of the population. The 5% line was crossed in 2005, likely never to be seen again.

Hunters tend to be an obstinate bunch. We have a history and legacy of hunting that is woven into the fabric of this country. This tradition has led us to believe we hold the high ground and we preach as if it is unassailable. But ‘us vs. them’ just doesn’t work when faced with the math. We must be conservationists first, caretakers of wildlife and wild places for all. That is the high ground. Hunting is not an entitlement, it is a privilege and responsibility.

On the bright side 70% of Americans still support hunting. That means there are over 200 million people who are not hunters yet still approve of the activity. Anti-hunters aren’t the growing force, the bump in the night. Sportsmen should not be lecturing about what divides us from the non-hunting public. We should be reaching out to the 200 million people in our corner, encouraging participation and talking about our love of the land and love for the birds. We should be the ones raising awareness for conservation issues and calling for a solution.

Upland bird hunters have an advantage many other hunting disciplines lack. We don’t cloak ourselves in camo or hide in trees or blinds. We hunt openly, putting ourselves out there. We cherish our bird dogs that are stoic, loyal and inspiring – ideals everyone longs for in people. We raise puppies as family members and they warm the coldest hearts and demonstrate our compassion for animals. We often hunt with the shotguns hung over fireplaces and admired by family members, passed down from grandfathers. We create beautiful scenes of pointing dogs and flushing birds. Upland hunters epitomize a tradition and legacy that non-hunters can witness and respect.

It’s time for new ideas and honest conversation about our roles as stewards of the outdoors. We need non-hunters as much as they need us. We need to talk about hunting in a new way that is inspiring, not divisive. It’s time to talk about conservation in an honest way. If we want to continue upholding the North American Conservation Model then it will take more than hunters to maintain the resources.

As we wrestle with the realities of conservation and participation, the downward trend for upland species continues the decades-long slide. The plight of upland birds and hunters are following the same path. Do we care enough about hunting traditions to take the steps necessary to see them continue? Are upland birds important enough to fight for their existence, even in far off places where we may ourselves never hunt? Debating our role does nothing to change the decline. In truth, the longer we wait to address it, the longer it takes hunters to unite and embrace our responsibility, the cost of replacing the lost resources climbs exponentially. Those who believe now is not a good time are ceding that they prefer longer odds and spending more later.