The Hunters’ Predicament

A couple of years ago I found myself hunting late season public lands in West Virginia. Having never hunted here before I took to talking to every resident I encountered, inquiring of bird numbers, conditions and terrain. This area is a fairly well-known stronghold for hunters and anglers, so it was shocking when I brought up hunting grouse it was met with oblivion. Even anglers in area streams and lakes, outdoorsmen, had no idea about this Ruffed Grouse of which I spoke.

A few weeks ago while sitting in a wildlife conservation conference listening to biologists talk in ’science speak’ of early successional forests and high biotic potential, the lightbulb finally switched on.

We are aliens.

Immersion in the outdoors and upland birds makes us incomprehensible to the average person. Even to the average hunter, much of what I say and do and how I say it is incoherent. I must sound like a madman hopped up on random CRP facts, bio-speak, species minutia dull enough to cure even the toughest case of insomnia.

This causes me to reconsider how to communicate and who the audience actually is. And this extends well beyond just hunting.

The majority of Americans do not participate in any outdoor activity. According to the Outdoor Industry Association’s 2018 Outdoor Participation Report just 49% of Americans took part in a diverse list of 45 outdoor activities. That is not to say that people don’t have a cerebral appreciation for wild places, it just means that most don’t step foot in them. They don’t bike, trail run or rock climb. Most Americans don’t camp or hike. And the vast majority – 96% – don’t hunt. 165 million citizens did nothing outside last year.

While many of us are defined by our involvement in the outdoors, the points of reference we share with half of all Americans are sparse.

In many ways beyond just outdoor brands and publications, everyone has become a content creator. Social media platforms give us all an audience to share our passion and interests. If we assume these social platforms reflect statistics of the general population it paints an interesting picture.

Because many of our friends and followers may be involved in similar activities, it can distort our own reality. An image of hunting shared on Facebook could be seen by 7 million other American hunters, which sounds like a large audience. But that same image is three times more likely to be seen by someone who knits — 24 million.

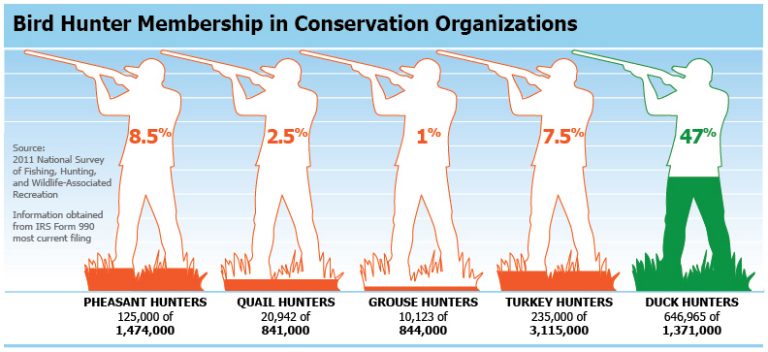

Outdoorsmen are a minority and hunters are just a tiny fraction of that.

I don’t know anything about knitting. You’d probably be hard-pressed to make me find an interest in it. But I can certainly appreciate the things that can be made with needles and yarn. And I admire the patience, effort and skill it takes to make your own hat, scarf and mittens. I suppose if I were giving advice to the knitting community of how exactly to make me care about knitting, I would say show me how to make something useful for me. Knit a shotgun sock? Though I’m still not convinced you could make me a knitter.

But maybe that short walk in knitter’s shoes sheds some light on the hunters’ predicament. Lots of hunters and outdoor advocates frame what we do in terms that resonate with our following: it’s legal, provides natural protein, manages wildlife population, funds conservation. But that reasoning likely means very little to anyone outside of the hunting community — some 312 million Americans.

The path to the broadest audience, to engage those who don’t hunt, is not photos and stories of dead animals. Take them on the journey, help them comprehend the process. Non-hunters can appreciate and benefit from seeing nature through those who have an inextricable connection with it. Beyond meat and management, the majesty of the outdoors is humbling. The limits of our own consequence are most apparent surrounded by landscapes unimpressed with intrusion.

We need more people who admire wild places. We need a majority of Americans vested in the outdoors. The hunting industry struggles to find ways to R3 (retain, recruit, reactivate) out of a funding model death spiral. But I find myself more concerned with simply having enough people actually care about the outdoors in meaningful ways. Tales of explosive Ruffed flushes from golden aspen cuts only ignite the imaginations of those who know what grouse and aspen are.

Before we ask people to appreciate hunting, tolerate it and accept our motives for pursuing and harvesting animals, we probably should be asking them to join us for a walk outside. The leap from zero outdoors exposure to hunting might just be a gap too wide to bridge.