Planning for the 2022 Upland Season

We are on verge of another upland season. Though preliminary plans started taking shape the the final days of the 2021 season, now is the time we really begin scrutinizing the schedule of prized days afield.

One of the biggest frustrations for upland travel hunting is arriving at a destination that doesn’t live up to the billing. There are ways to minimize that risk — local contacts, wildlife department bird biologists, upland game forecasts. But only you know your hunting methods and goals in the uplands. Relying on someone else to understand and translate those objectives to conditions on the ground can be dicey.

Public land/ private land, early season/ late season, experience level of the hunters, skill level of the dogs, fitness levels — all these elements can have a huge impact on your time afield and offer wildly different outcomes, even while hunting in the same general area of other uplanders.

There’s a satisfaction in researching and planning an upland adventure. Though I’ll take data and input from others, I like to rely on my own experience and knowledge for final decisions.

Weather is the biggest factor in upland bird density. It effects habitat and cover, food sources and mortality rates. Weather extremes tend to be bad for game bird populations — too wet, too dry, too hot, too cold — all tough on birds.

Throughout most of the spring and summer I keep an eye on the drought monitor. Areas experiencing a lack of precipitation in the spring can result in low insect counts, a source of protein and ultimately survival for hatchlings. If drought persists later into spring and summer months, then the cover and habitat that protect gallinaceous birds through the season can be compromised.

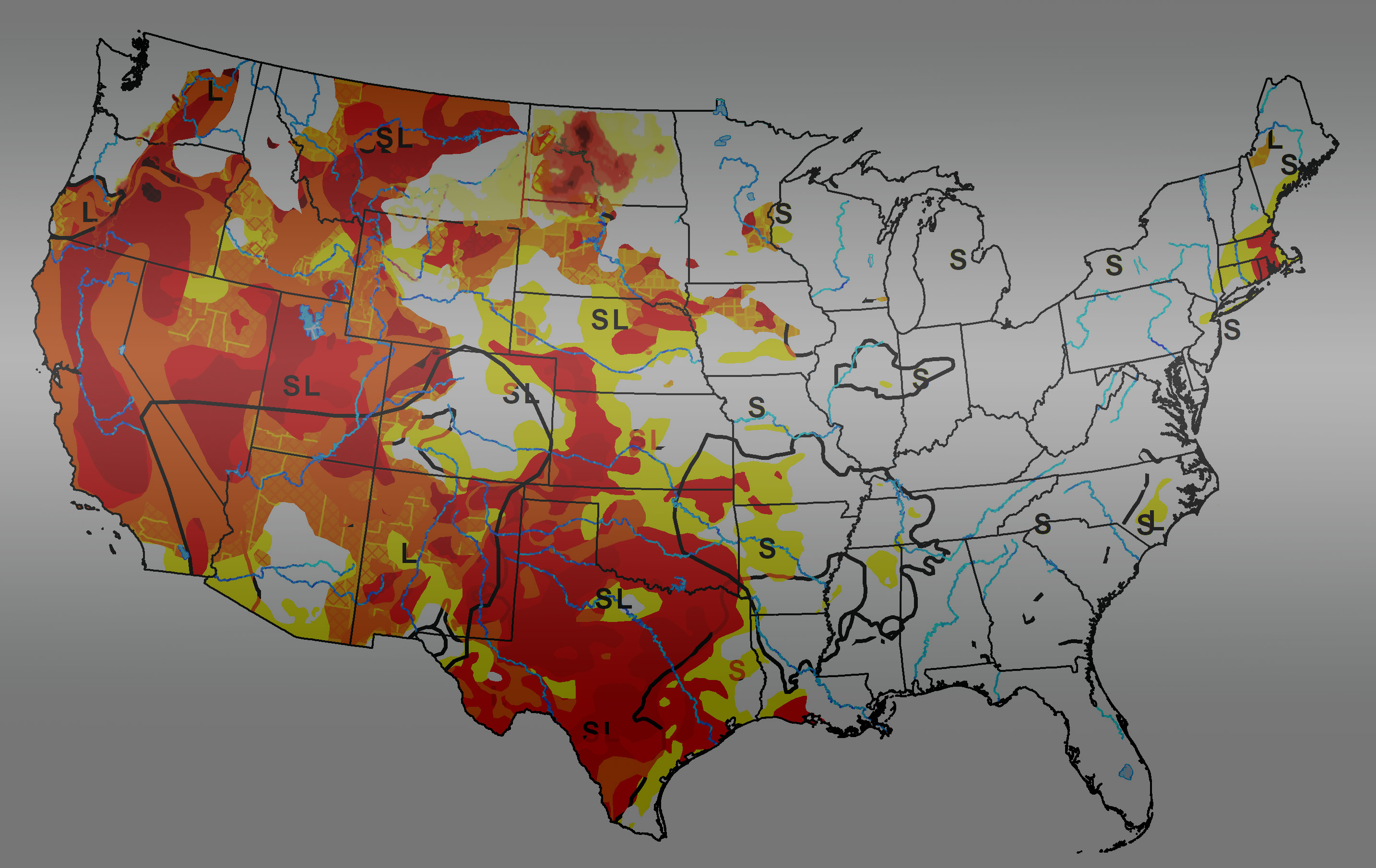

A look at the US Drought Monitor maps — fall of last year, spring and most recent — shows a pretty stark picture. Much of the west has been experiencing a severe lack of precipitation. If you ended up hunting some of these red or maroon areas last year (August 2021 map) you likely noticed a scarcity of birds. We spent time in multiple red zones, and birds numbers were definitely negatively impacted.

In many areas the drought continued well into the spring (April map). Yellows and light oranges on these maps don’t represent persistent drought. Warm and dry conditions during nesting can actually be beneficial to a hatch.

By late summer of this year, there are a few bright spots — Colorado, the Dakotas, Montana, much of Idaho, Washington, Wyoming have exited drought status. Did the drought in these areas subside early enough to produce a decent crop of hatchlings? Tough to say. These maps tend to paint areas with a broad brush and in reality weather is very micro-climatic. Just because it hails in one part of the county, doesn’t mean it hailed in the entire county (yes, hail can have a huge impact on nests and young birds).

Arizona, Nevada, Oklahoma, Oregon, parts of New Mexico, Texas and Utah are all in persistent drought that’s lasted in many cases for over a year. That’s not good news for upland bird populations in these areas.

Much of the Midwest and states east of the Mississippi have fared well with rainfall.

We also track the acreage enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). Not all land in the CRP program allows hunting access, the acreage is still privately owned. But many states have walk-in access programs which tap land owners enrolled in CRP. This is a way for those landowners to increase revenues on under-contract acreage. States generally pay a small stipend per acre to gain access for hunters.

We review the CRP Emergency Haying and Grazing Map to better understand the conditions we can expect for walk-in access programs. If a county is designated high-level drought where there is at least 40 percent loss in forage production, the USDA will declare that county’s CRP eligible for haying or grazing. This is a protection for livestock producers enrolled in the CRP program.

The latest map shows a few bright spots — the Dakotas, Idaho, Iowa, Minnesota, Montana, Washington and Wyoming have many counties which no longer qualify for emergency haying (as indicated by the bright green color). But the bigger story is that still nearly half of the country’s CRP acreage qualifies for emergency haying. That doesn’t guarantee that all qualifying acres in a CRP/ walk-in program will be hayed or grazed. But from personal experience, in eligible counties, 9 out of 10 contracts will take advantage of the designation and bail or graze the native grass. You’ll recognize this when you roll up to a plot enrolled in a state access program and the land is barren and lacking any cover. Many bird hunters who hunted public access lands in North Dakota and South Dakota last year became painfully aware of emergency haying practices.

Snowfall totals and freak storms also factor into our upland plan. If a winter is exceptionally hard or cold, it doesn’t bode well for over-winter survival leading into spring breeding and nesting. The ’21 winter wasn’t exceptional by most standards across much of the country. But, there was a freak April storm that brought extreme cold and dumped 20”+ of snow on Montana and the Dakotas. That storm certainly effected game birds and may have had a negative impact on prairie grouse leks.

What does it all mean for our upland plans?

Generally speaking I don’t chase bird forecasts (partly because I don’t have full faith in them and partly because the heft of the game bag never matters to me). But this year we’ve got a new pup and new pups need lots of bird exposure.

I take all the info, talk to all my local contacts and then try and pull together the best plan for how we’ll approach the season.

If we overlay all these “bad color” maps, the result shows the places that aren’t going to have great cover or great bird density this season. You probably won’t find us there. OR maybe the puppy catches on quickly and we decide to test ourselves in extremely challenging conditions.

Wishing everyone a great season. Plan well.

Very few states actually do harvest surveys and/or roadside counts of upland birds. Iowa and North Dakota still seem committed to providing accurate information.

Much of the info from spring surveys won’t become publicly available until early September.

I live in Southern Nevada and I’m headed up for the Snowcock opener September 1st.

The stats the NDOW gamebird Biologist gave me from the 2021 surveys are 150 hunters took out the free permit, 50 hunted for a total of 154 days (three day average) 3 birds bagged, one lost .

Last year I was up to the Ruby’s late, got caught in a freak snow storm and made it out. My eighth trip for the birds, shot a mature Snow cock in 2016. I choose to not take my dog this year, I just can’t get them safely to a couple of my best spots. At 65 maybe my last try.

Will try for three days hunting, before dropping down for Blue Grouse.

More pertinent to the article, late Monsoon rains here in Southern Nevada, another bad years for Gambels, NDOW reduced the bag limit to 5.

Later up to Idaho for Pheasant opener and work my way back for quail,huns,chukar

Winter over to Inyo N.F. for Mountain quail.

Sounds like a great season in the works.

Last I checked the historical average for Snowcock harvest was somewhere close to 3%. It truly is one of the most challenging hunts in this country. Most people don’t use dogs, I prefer the company. I think the long term drought in that area is gonna have a negative impact on those birds as well.

Thanks for the info on the Gambels, I think I missed the bag reduction.

My husband is searching for places to hunt wild birds in the 2024 season in Michigan. Open land only. Do you have any recommendations for that area? He’s been on FB chatting with other hunters, however a lot of them are just being rude and telling him not to come there. Also, if you know of any way to get info, that would be appreciated. Thanks!

2024, still plenty of time for planning.

Between National Forest and state lands, there are tons of public access areas to chase wild birds in the state. I would recommend getting him an OnX Hunt subscription for the state of Michigan for his smartphone. With that, he will be able to see all the public access areas. Also because grouse are highly dependent on early successional forest, there’s a layer that can be turned on that shows recent timber areas / year they were cut.

Another great resource, call the biologists at National Forest offices. They often have the most recent timber maps and can help share bird forecasts and drumming counts from specific areas. Michigan is a big state with tons of public access, so I’d look at narrowing the search based on where he believes he wants to stay and then look for the right age of forest (8-15 years IMO).

Born and raised in Michigan, I lived there until 2007 then moved to Idaho to hunt and had second career.

In Michigan I moved all over the lower peninsula for my career (DNR) I always had a cabin in Northern Newaygo county. I hunted extensively in Newaygo, Lake and Oceana counties. Each county has plat maps available usually through county extension offices. Many of the parcels were planted to Red pines years ago ago and quite worthless for any game. Others are large stands of Oak and hardwoods, also not much for birds, although good for squirrel and deer. But there are small parcels with good habitat for both Grouse and Woodcock. I used to color code my plat books as to what the quality of the habitat.

My wife and I moved back to Michigan in 2019 thinking it would be a good move for old age, after being in the West we didn’t like it at all and ended up moving back West to Southern Nevada. Brian if you pass on my email to Denise, I’ll be glad to help her husband maybe find some areas.

As for the 2022 Snowcock opener here in Nevada, I hunted Lamollie canyon East side 2 days, hiked in day before opener. It was like Springtime above 10,000 feet, flowers in bloom, lots of berries and water.

Good for the Snowcock but not for the hunter, they could stay up in the ledges inaccessible. In addition it was hot even at the high altitudes. I never say never and may do the hunt again.

Starting to cool here in Southern Nevada, time to walk the Mesquite for doves, good practice.