Making the Upland Stamp Work

Most of us who spend our time outdoors agree that something is going wrong for game bird species. It’s difficult to imagine the landscapes we know as no longer offering an opportunity to seek or enjoy upland birds. The steep decline experienced by many upland species isn’t the first time in history we’ve faced the prospect of losing abundant game. The American wildlife legacy and hunting heritage might have ended toward the end of the 19th century as a number of species faced extinction due to market hunting. If it weren’t for the emergence of what came to be known as the North American Model of Fish and Wildlife Conservation, we would not have the opportunity to hunt freely or enjoy wildlife.

The North American Model followed an 1842 U.S. Supreme Court decision that decreed that wildlife belongs to the people, with opportunity for all, and not government, corporations or individuals. The Model provides for and directs the proper use and management of the wild resources for which we are all responsible as well as prohibits the harvesting of wildlife for commercial markets. When wildlife restoration efforts failed in the early 20th century, it was the united efforts of sportsmen who went to work to fund the restoration of habitat and the protection of wildlife that successfully restored wildlife across the country. It can happen again.

On March 5, 2015, Ultimate Upland introduced a petition for the Federal Upland Stamp for upland habitat conservation in the article, It’s Time for a Federal Upland Stamp. The article brought about heated discussion on what an Upland Stamp managed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service would mean to hunters, how it would work, whether it would work, or why it would never work. Some do not want to pay “another cent” to conserve the habitat required to sustain upland birds. Some will only pay if there are guarantees on how the funds are spent. On the opposite end of the spectrum, some are willing to pay such a high price that it may exclude the average hunter.

Historically, it has been those of us who hunt and shoot who have supported the cost of wildlife management. Perhaps ironic to the anti-commercial aspect of the Model, commerce in hunting has resulted in a fundamental success in wildlife restoration. The best example is Pittman-Robertson, an excise tax on firearms, ammunition and archery equipment that is returned to state wildlife agencies for projects to restore, enhance and manage wildlife. Funds may be used to acquire and manage wildlife habitats, provide public use that benefit from wildlife resources, conduct state hunters education programs, and construct, operate and manage recreational firearm shooting and archery ranges. The future of bird hunting in America may depend on a similar program brought by sportsmen who wish to make conserving upland bird habitat a priority for states by creating a dedicated source of funding.

How Could a Federal Upland Stamp Work?

There are several reasons an Upland Stamp cannot follow the Duck Stamp model even though it replicates its pattern for success. The benefits of an Upland Stamp include an educational aspect and opportunity to highlight the cultural value of upland game species to broader audiences. But, the question asked is: How would it work when most upland game are non-migratory and are not a federal trust species? How would it work when most bird enthusiasts who would support the concept of the Upland Stamp wish for management authority to stay with the states?

The Wildlife Restoration program (Pittman-Robertson) serves as perhaps a better management framework for the Federal Upland Stamp. The Program has been a stable funding source for wildlife conservation efforts for over 75 years and provides states with matching grant funds based on the area of the State (50%) and the number of paid hunting license holders (50%). According to the Sport Fish and Wildlife Restoration Fund Report, excise-tax collections from 1970 to 2006 averaged $251 million per year. No State can receive more than 5% or less than .5% of the total funds made available and must meet a 3 to 1 matching requirement or fund at least 25% of the project costs from a non-federal source (for every $1 spent by the State, the State receives $3 from the fund). Funds are protected and must remain available until expended, meaning that they cannot be diverted for other purposes.

If the Upland Stamp followed this model, it acts as a long-term source of dedicated funding for the conservation of upland habitat that not only preserves State management authority but encourages states to undertake projects benefiting upland game species. The funds require use for acquisition, restoration or conservation of upland bird habitat. Protections against the use of funds for any other purpose, including opposition to the taking of game result in the same penalties as included in the Pittman-Robertson Act. The allocation methodology is based on landscape-scale habitat needs, population of bird species, or another variable that maximizes the impact of stamp funds. The matching component and period in which funds are allowed to be utilized incentivizes states to use the funding to prioritize upland bird projects.

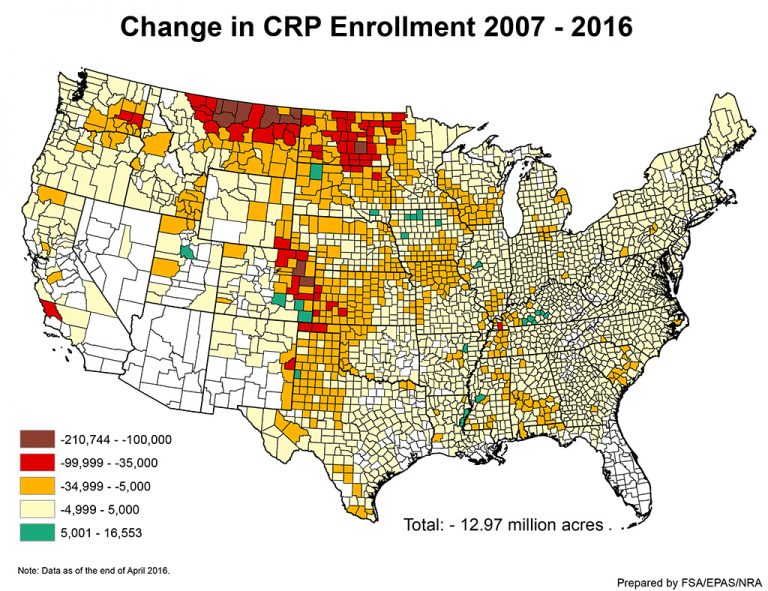

There is little argument that our landscapes are forever changing as we face the loss of some of our most iconic game bird species with many species experiencing a 40% rate of decline in the last 40 years. Loss of habitat is the primary cause, and a solution originating from sportsmen is the best chance we have to save our upland bird heritage. Upland hunters have a unique understanding of why upland conservation must be a priority, and we have an opportunity to take responsibility for the wild resources that belong to all of us. They have been held in our trust.

Join us in calling for the creation of the Federal Upland Stamp and be a part of conservation and grassroots history.

*Photos by Craig Armstrong

We do not need another federal fee! The idea is is a pocket filler. Such as every other pet project in this country. Leave conservation to each state like it should be.

As Christine has pointed out, this could/would function at the state level. The cost of conservation continues to increase and the trajectory of upland species is on a 50+ year decline. State budgets are strained and small game often gets pushed to the bottom of a long list of funding requests.

Small thinking get’s us nowhere. It’s time for big ideas and new solutions.

If we keep doing what we’re doing, we’ll keep getting what we’ve got. And that’s not good enough.