Backyard Bobwhite: Part 1

Is the key to restoring quail right out your back door?

I grew up in small farming community in rural Northeast Ohio. It’s not considered an upland bird hot spot. But I still remember seeing wild quail when I was a kid. And I’ve verified this with others from the area. Bobwhite used to inhabit the hedge rows and fence lines.

Then came the blizzard in January of 1978. In Ohio it produced wind speeds of 70+ mph and wind chills dropped below -60° F. Depending where you lived the snowfall reached over 30″ with drifts that were epic. I remember digging a snow tunnel directly out the backdoor that I could stand up in (I was still just a little guy). This storm killed over 50 people in the state of Ohio. It also killed nearly every quail. And their comeback has been slow to nonexistent.

There’s still a Bobwhite hunting season in 16 Ohio counties primarily in the southwest where populations have hung on. The Ohio DNR has taken shots at expanding these quail territories by trapping live birds in areas of Ohio with decent population and seeding them to counties further north with cooperation from private landowners. The state also has attempted restoring Bobwhite on public lands by transplanting wild birds trapped in Kansas. Those seem like good plans but public funding for this type of program is getting sparse. Quail aren’t the high-profile, high-draw return on investment that big game and turkey are these days.

Bobwhite Quail range tends to expand at a snail’s pace, by most accounts about 1/4 mile per year. With annual mortality rates above 80% it could take centuries under the best case scenarios for quail of southern Ohio to populate the rest of the state. That’s not going to happen on public land alone.

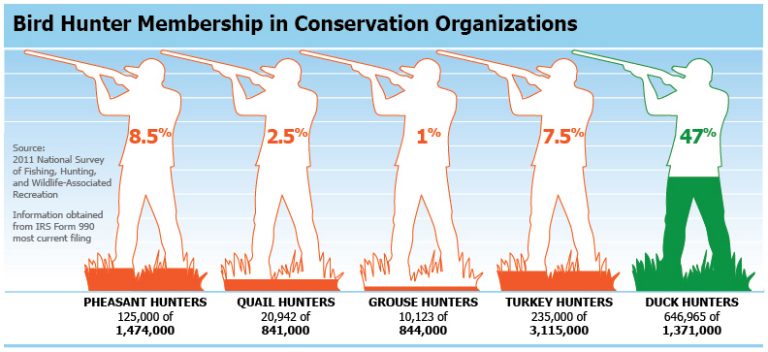

Every year we receive messages and posts from fans asking what they can do to help conserve upland birds. And the stock answer always seems to be pay dues to the large conservation organizations, and attend their banquets. But dues and banquets leave many unsatisfied. Cutting a check doesn’t make some feel invested in conservation.

Chapters of Pheasants/ Quail Forever are active and do good work attracting people to upland sports. But the focus in this area seems to be improving hunting habitat on public lands where wild birds don’t exist. When birds are released into these tracts the hunting might be wonderful, the bird survival is another story.

That’s bothered me.

And that’s when the wheels started turning. How does someone who doesn’t own massive tracts of land or have millions of dollars positively and actively impact upland bird conservation?

Bobwhite are the perfect candidate species for micro-conservation. They are small birds, with relatively small resource requirements that prefer a home territory.

Most of my childhood was spent on our family farm. My parents still live there. My dad taught my sisters and I how to mow around the age of 11. He’d gas up the mowers and turn us loose to shear the 8 acres that run around the house, outbuildings and orchard. It was a biweekly chore during the summers. Now that we’re all grown the mowing has fallen back to dad and now he’s recruiting the grandkids.

But those new recruits have sports and swim meets and much more important pulls on their time that require a granddad to attend that make a manicured lawn seem less important. And dad is no longer a spring chicken.

This winter we began hatching a plan to lighten the mowing load and reintroduce the Bobwhite back to our homestead without breaking the bank. The goal is to map out steps for an individual (or two) to run their own habitat and reintroduction process with minimal land requirements. We’ll document all costs, obstacles and success or lack of. And if all else fails at least dad will have less to yard to upkeep.

We identified an area at the back of the farm totaling around a half-acre that dad is willing to give up mowing. This plot sits between a small old orchard and two sets of evergreen trees. It offers great cover from the elements, a nearby creak for water and is close enough to the house to limit exposure to predators as well.

The first step is to return it to good quail habitat . In Ohio the largest obstacle for quail success is access to food over the winter. There’s still plenty of grain agriculture around, but cover along fence lines that have been traditional habitat is becoming non-existent. Commodity prices are too high for farmers to allow land to sit untilled. But lawns, good lord there are plenty of manicured yards. If farming is going to take up the quail’s habitat then let’s give it back one square foot of lawn at a time.

I am a bird hunter, not a biologist. But I know a thing or two about these birds that I’ve pursued for decades. I know the types of areas and habitat where the dogs and I have found quail. With a little tilling and cultivation we can transform yard into that type of area. It won’t fulfill all the requirements of a Bobwhite’s life cycle. But by my account most of those requirements they can still fulfill on their own. The winter food source close to good cover is the crux in this state.

The week prior to Memorial Day we tilled our plot and hand seeded a game bird mix containing sunflower, millets, and sorghum seed. We also took down an old apple tree that’s been crowding some pears in the orchard. We utilized those limbs to stack three massive brush piles for the birds to eventually use as dense protective cover. The hope is this will become the home base for our quail, putting everything they need within a very small area so that they have every motivation to stay and thrive.

It was a full day of hard work. And now there is more to come.

But that’s for the next installment: Making a cost effective quail pen and our plans to train pen-raised quail for survival in the wild.

Good luck! I’m doing the same thing on a little bigger scale on 160 acres I own in Nebraska. I have a few wild pheasants and quail and have recently planted two plots of a wild bird mix similar to yours as well as some red clover. My hope it the red clover will attract insects for brooding chicks to eat and the bird mix will help the existing birds survive better through the winter. I look forward to seeing updates on your progress.

Sounds like you’ve got a great start out there Duke! The clover for spring is a great idea. Before we invest in a spring planting we’re trying to make sure we can get some birds to survive the winter.

Good luck and let us know how your plots turn out. We’ve hunted Nebraska a number of years and have always felt that a bit of habitat could go a huge way towards improving numbers in the state because you still have wild populations.

I am curious about how your quail project worked out.

I too can remember when we had decent populations of upland birds in northeast Ohio. It wasn’t just the winters of 77, 78. The decline in their populations has been most significantly caused by drastic changes in agriculture practices and technologies. Back in the 70’s and before corn fields were not cut down to silage and a variety of grasses and weeds grew among and in between the rows. Farm harvesting equipment was such that picked fields always had at least small amounts of unpicked or scattered grain on the ground. Today those same fields are barren with only short corn stubbles left in the ground and near zero waste grain on the ground. This has also had an effect on waterfowl hunting as those birds have less reason to stop over during migration. I’m my opinion there needs to be wide spread change in the way landowners manage their properties so as to allow at least a small percentage of grasses and brush maintained at least along the edges of the properties. Until these sorts of changes can be implemented upland Wildlife populations will only continue to decline.

Even with our limited resources and lack of “professional” experience, the birds we released made it well into the following year per neighbors’ sightings and photos. If we had the financial backing for GPS trackers, it would have been helpful, but we know for certain the birds traveled that creek corridor for much greater distances than we expected, to the tune of a couple miles.

In order for longer term success (successful breeding in the spring and a truly wild generation) we would need much higher density of release, more birds able to locate and regroup. Our releases were just really small scale.

Modern farming practices certainly have an impact, the ones you mention but also “Roundup Ready” crops that encourage the use of glyphosate.

How do you convince landowners with big property tax bills and expenses to lessen their ROI? There’s the problem. If there were tax credits or mechanisms that would incentivize landowners to benefit wildlife, then you’d probably see that happen. At one time, the CRP program was this mechanism, but it’s been made so complex and convoluted over iterations of rewriting the Farm Bill, that it no longer has the same impact. (You can’t have 2/3 of the acreage enrolled nationwide in any given year placed into emergency haying/grazing status – which is exactly what has happened the past two years.)